AI Ethics Brief #94: FRT in Canada, gender in military AI, bias in toxic speech detection, and more ...

What is delivery apps' obsession with ratings and how is it creating harm?

Welcome to another edition of the Montreal AI Ethics Institute’s weekly AI Ethics Brief that will help you keep up with the fast-changing world of AI Ethics! Every week we summarize the best of AI Ethics research and reporting, along with some commentary. More about us at montrealethics.ai/about.

⏰ This week’s Brief is a ~25-minute read.

Support our work through Substack

💖 To keep our content free for everyone, we ask those who can, to support us: become a paying subscriber for as little as $5/month. If you’d prefer to make a one-time donation, visit our donation page. We use this Wikipedia-style tipping model to support the democratization of AI ethics literacy and to ensure we can continue to serve our community.

*NOTE: When you hit the subscribe button, you may end up on the Substack page where if you’re not already signed into Substack, you’ll be asked to enter your email address again. Please do so and you’ll be directed to the page where you can purchase the subscription.

This week’s overview:

✍️ What we’re thinking:

Battle of Biometrics: The use and issues of facial recognition in Canada

Does Military AI Have Gender? Understanding Bias and Promoting Ethical Approaches in Military Applications of AI

🔬 Research summaries:

Handling Bias in Toxic Speech Detection: A Survey

Why AI ethics is a critical theory

Robustness and Usefulness in AI Explanation Methods

📰 Article summaries:

Delivery apps’ obsessions with star ratings is ruining lives

The secret police: Cops built a shadowy surveillance machine in Minnesota after George Floyd’s murder

The War That Russians Do Not See

📖 Living Dictionary:

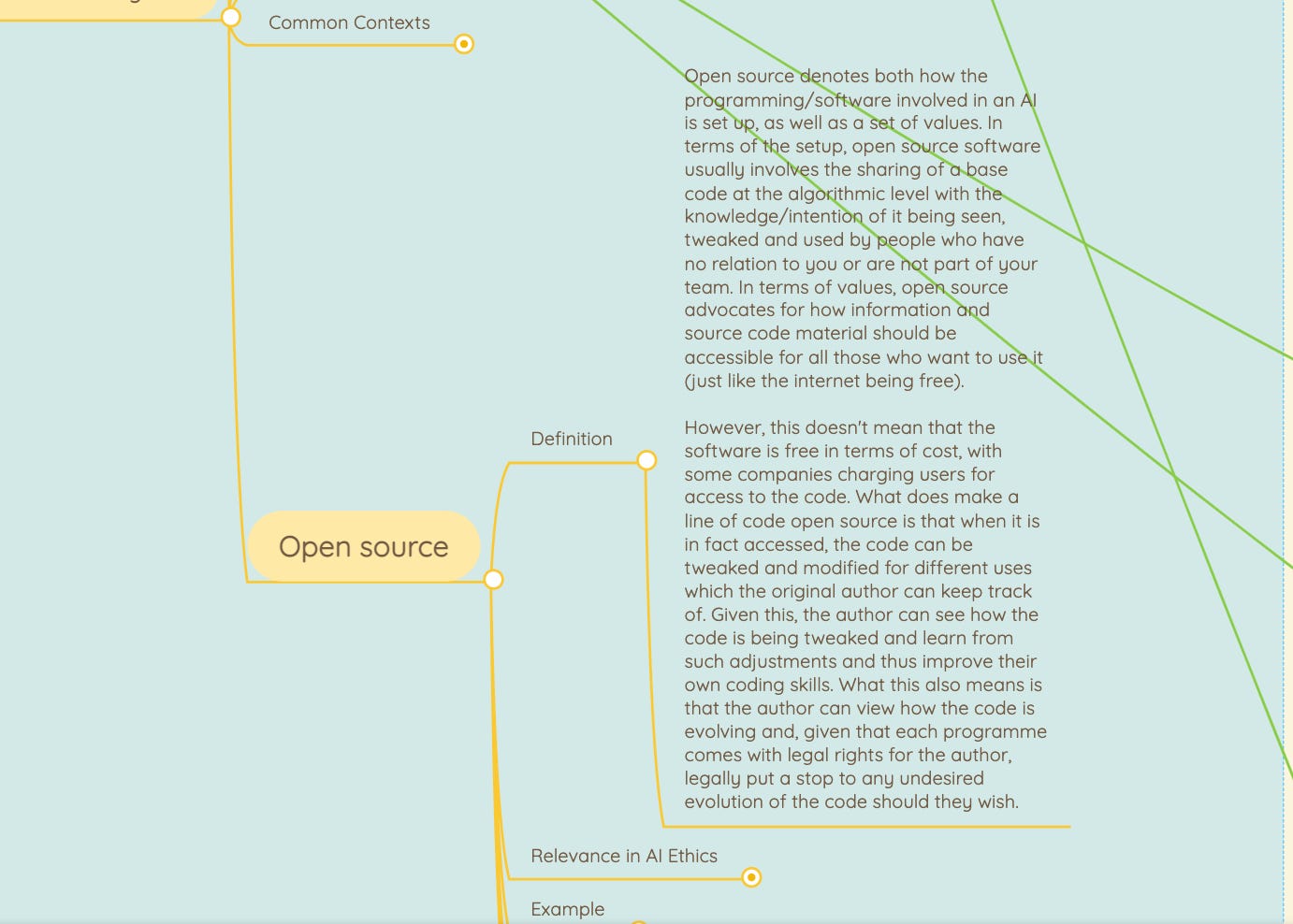

What is open source?

🌐 From elsewhere on the web:

Abhishek vs. Terminator (Important Not Important Podcast)

💡 ICYMI

Rethinking Gaming: The Ethical Work of Optimization in Web Search Engines

But first, our call-to-action this week:

What can we do as a part of the AI Ethics community to help those who are suffering in the current war in Ukraine? We’re looking for suggestions for example on tips (actions that we can all take) to prevent the spread of misinformation, better understanding of the deployment of LAWS on the battlefield, etc.

✍️ What we’re thinking:

Battle of Biometrics: The use and issues of facial recognition in Canada

Facial recognition (FR) is the confirmation of an individual’s identity through images of their face and has become an increasingly popular form of identification through the use of biometric data. Biometric measurements are not new forms of technology; rather the uses of biometric data have increased over time and become new to public consciousness. FR, first created during the Cold War, has been used in a variety of identification and surveillance manners. Seen as an innovation in computer science and machine learning automated processes, FR is an evolution of the late-nineteenth-century introduction of measurements, mapping, and analysis of biometric information. [1] The long history of FR technology shows how biometric data has permeated modern society, with artificial intelligence becoming a regular part of life rather than a fictional anomaly. The use of FR is a controversial topic due to ongoing debates surrounding privacy, biases, abuse of power, and the uneven balance of costs and benefits. The unknowns surrounding the uses of FR and the possible threats on a national and international scale make the implementation of FR systems a highly controversial topic in need of further regulation. Many controversies surrounding FR come from police use of technology to identify criminals.

To delve deeper, read the full article here.

Gender, as scholars have long argued, is part and parcel of existing power relationships. This means that the aims of gender equity cannot be limited to proportional representation of gender identities (though, of course, this is an important goal), but should also consider how being and knowing are coded by gender. Ostensibly neutral terms–like rationality, AI, machines or data–tie to and reproduce gender. For example, in debates on robotics, masculine stereotypes are utilized to suggest the potential dominance of “technical” systems, while feminine stereotypes prevail in showing the ways the systems might be controlled. These tropes are scaled up through references to “hard” and “soft” knowledge. Such masculine and feminine figures are simultaneously coded through race, sexuality, age and ability.

To delve deeper, read the full article here.

🔬 Research summaries:

Handling Bias in Toxic Speech Detection: A Survey

When attempting to detect toxic speech in an automated manner, we do not want the model to modify its predictions based on the speaker's race or gender. If the model displays such behaviour, it has acquired what is usually referred to as "unintended bias." Adoption of such biased models in production may result in the marginalisation of the groups that they were designed to assist in the first place. The current survey puts together a systematic study of existing methods for evaluating and mitigating bias in toxicity detection.

To delve deeper, read the full summary here.

Why AI ethics is a critical theory

Analyzing AI ethics principles in terms of power reveals that they share central goal: to protect human emancipation and empowerment in the face of the powerful emerging technology that is AI. Because of this implicit concern with power, we can call AI ethics a critical theory.

To delve deeper, read the full summary here.

Robustness and Usefulness in AI Explanation Methods

Given the hype received by explainability methods to offer insights into black-box algorithms, many have opted-in to their use. Yet, this work aims to show how their implementation is not always appropriate, with the methods at hand possessing some apparent downfalls.

To delve deeper, read the full summary here.

📰 Article summaries:

Delivery apps’ obsessions with star ratings is ruining lives

What happened: At one point or another we’ve all used some sort of a food delivery app, and our decisions on which restaurant to pick factors in ratings that we see on the app. This article shows us the other, dark side to what ratings do to restaurants owners. In a dramatic case highlighted in the article, a restaurant owner collapsed from a brain hemorrhage after trying to placate an irate customer to keep them from giving a negative rating on the food delivery app. The owner died shortly after being hospitalized. The ratings system exerts undue pressure on restaurant owners to the point that they host “review events” with giveaways to entice customers to rate them positively. More perniciously, it has created a gray market for fake reviews to prop up clients’ restaurants while disparaging those of competitors.

Why it matters: The genesis of the ratings system was meant to serve as a guide for customers to find restaurants with great food and experiences, while incentivizing restaurants to uphold standards. But, it has devolved into a gamified environment where restaurants jostle to get as high a rating as possible, yet not too high as to appear fake, while customers can use this unfairly to their advantage to penalize restaurants where their expectations aren’t fully met. The article highlights the plight of merchants who find the system to be repressive in that it skews heavily in favor of the customer with few recourses for the merchants with dismal support from the companies that own the food delivery app.

Between the lines: As we digitalize more and more aspects of our lives, we have to incorporate thinking about the second-order effects all of this has on our lives. In particular, a single interaction, forced by the delivery platform to placate a customer otherwise risk losing their standing with the platform had a very real, physical impact on the health of the restaurant owner that ended with their demise, should give us pause to consider what role we as consumers play in propping up such an exploitative system. There is human labor behind the algorithmic veneer that smoothes our interactions with the world, bringing convenience to our doorsteps with just a click or tap. Systems thinking might offer us a pathway to build AI-enabled systems that take these human considerations into account.

What happened: Investigations done by the team at the MIT Technology Review reveal glaring details behind Operation Safety Net (OSN), a high-tech enabled surveillance infrastructure, being pervasively used in the US with support from federal agencies working in consort with local police forces. The extent of high-tech including facial recognition, a data portal, field app, and geofence data show how intrusive and vast the information collected by the agencies under the guise of public safety. More so, OSN was supposed to be time-boxed and dismantled, but as we’ve seen time and again with the introduction of any new technology, once it has been deployed, it becomes incredibly difficult to roll it back.

Why it matters: Highlighting constitutionally guaranteed rights, the article makes the case that without a degree of anonymity, there is an infringement of fundamental rights in people being able to freely and legally organize and participate in protests. The risks with real-time data-sharing apps that form a part of the OSN infrastructure allow law enforcement officers to have instant access to who is present and their histories and other information risking their safety rather than protecting their fundamental rights.

Between the lines: Something that stood out in the article was that the surveillance captured through Predator drones flown over cities, typically used in war zones, was inferior to the data that was gathered through the OSN. More so, having mobile apps that are available to field officers on the ground amplifies the impact of the gathered information. Finally, the fact that the OSN continued far beyond the publicly declared mandate and carried out its activities in secret, ironic to its mission to protect public safety, shows that the work carried out by organizations such as MIT Technology Review is essential to ensure the protection of fundamental rights, especially when they might be subverted without the knowledge of the people.

The War That Russians Do Not See

What happened: Owing to an aging demographic that prefers to get its news from traditional TV, a segment of the Russian population, specifically older population, continues to be disconnected from the real discourse on the war in Ukraine. They are exposed only to state-created and sponsored material on controlled TV channels broadcasting narratives and images that are severely disconnected from the realities of war taking place on the ground. In some cases, the imagery being broadcast and the voice-overs are clearly disconnected. The flow of this kind of propaganda remains constant and is only interrupted with other benign shows, often resuming to cover the war in Ukraine with posturing that showcases Russian aggression as supportive intervention.

Why it matters: The fragmentation of people’s views even within the same country, based on the kind of media that they access is problematic, especially when it consists of people who have no alternative sources of information that they might explore. It is also problematic since the older demographic that is more susceptible to this kind of propaganda is also the one that has grown up with tropes supplied to them of Western domination and victimization of Russia post WWII. As the article mentions, “[d]ays before the full-scale invasion began, the Levada Center asked Russians who they thought was responsible for the mounting tensions in Ukraine. Three per cent blamed Russia, fourteen per cent blamed Ukraine, and sixty per cent blamed the United States.” This is emblematic of how such propaganda can be successful in diverting attention from real issues.

Between the lines: Information operations are not new, especially not in Russia. With the ease of generating and distributing content, even on traditional outlets like state TV, the scale of harm continues to remain unmitigated, especially as the chasm between the reality of war on the ground in Ukraine and what is broadcast about the degree of involvement and Russia’s aggression remains unchallenged. Higher rates of media literacy, particularly for those who are in older demographic groups and more susceptible to the broadcasted narratives, will be critical if there is to be any sort of meaningful pressure from Russia’s own population in changing course. This also points to broader trends whereby we need to elevated digital and media literacy if we want to achieve meaningful engagement from citizenry in key issues of the day. Good journalism and people’s awareness of that journalism will be a key first step in that fight.

📖 From our Living Dictionary:

What is open source?

👇 Learn more about why it matters in AI Ethics via our Living Dictionary.

🌐 From elsewhere on the web:

We need to design and implement standardized AI ethics regulations across everything AI touches, so, everything, while also asking questions like: what is “ethical”? And who gets to decide? And why do they get to decide? And how are they incentivized to decide, in today’s society? And who provides those incentives? Who gets to regulate all of this? Who elects the regulators? And how do we make sure companies actually implement all of this? These are among the most important questions of our time, because AI touches everything you do. The phone in your hand, your insurance, your mortgage, your flood risk, your wildfire risk, your electronic health record, your face, your taxes, your police record, those Instagram ads for the concerningly comfortable sweatpants, your 401k – some version of AI, whether it’s the AI we always thought was coming or not – is integrated into every part of your life.

💡 In case you missed it:

Rethinking Gaming: The Ethical Work of Optimization in Web Search Engines

Through ethnographic research, Ziewitz examines the “ethical work” of search engine optimization (SEO) consultants in the UK. Search engine operators, like Google, have guidelines on good and bad optimization techniques to dissuade users from “gaming the system” to keep their platform fair and profitable. Ziewitz concludes that when dealing with algorithmic systems that score and rank, users often find themselves in sites of moral ambiguity, navigating in the grey space between “good” and “bad” behavior. Ziewitz argues that designers, engineers, and policymakers would do well to move away from the simplistic idea of gaming the system, which assumes good and bad users, and focus instead on the ethical work that AI systems require of their users as an “integral feature” of interacting with AI-powered evaluative tools.

To delve deeper, read the full summary here.

Take Action:

What can we do as a part of the AI Ethics community to help those who are suffering in the current war in Ukraine? We’re looking for suggestions for example on tips (actions that we can all take) to prevent the spread of misinformation, better understanding of the deployment of LAWS on the battlefield, etc.